Huawei Technologies Co., the world’s largest telecommunications company, dominates African markets, where it has sold security tools that governments use for digital surveillance and censorship.

But Huawei employees have provided other services, not disclosed publicly. Technicians from the Chinese powerhouse have, in at least two cases, personally helped African governments spy on their political opponents, including intercepting their encrypted communications and social media, and using cell data to track their whereabouts, according to senior security officials working directly with the Huawei employees in these countries.

In Kampala, Uganda, last year, a group of six intelligence officers struggled to contain a threat to the 33-year regime of President Yoweri Museveni, according to Ugandan senior security officials. A pop star turned political sensation, Bobi Wine, had returned from Washington with U.S. backing for his opposition movement, and Uganda’s cyber-surveillance unit had strict orders to intercept his encrypted communications, using the broad powers of a 2010 law that gives the government the ability “to secure its multidimensional interests.”

According to these officials, the team, based on the third floor of the capital’s police headquarters, spent days trying to penetrate Mr. Wine’s WhatsApp and Skype communications using spyware, but failed. Then they asked for help from the staff working in their offices from Huawei, Uganda’s top digital supplier.

“The Huawei technicians worked for two days and helped us puncture through,” said one senior officer at the surveillance unit. The Huawei engineers, identified by name in internal police documents reviewed by The Wall Street Journal, used the spyware to penetrate Mr. Wine’s WhatsApp chat group, named Firebase crew after his band. Authorities scuppered his plans to organize street rallies and arrested the politician and dozens of his supporters.

The incident in Uganda and another in Zambia, as detailed in a Journal investigation, show how Huawei employees have used the company’s technology and other companies’ products to support the domestic spying of those governments.

Since 2012 the U.S. government has accused Huawei—the world’s largest maker of telecom equipment and second-largest manufacturer of smartphones—of being a potential tool for the Chinese government to spy abroad, after decades of alleged corporate espionage by state-backed Chinese actors. Huawei has forcefully denied those charges.

The Journal investigation didn’t turn up evidence of spying by or on behalf of Beijing in Africa. Nor did it find that Huawei executives in China knew of, directed or approved the activities described. It also didn’t find that there was something particular about the technology in Huawei’s network that made such activities possible.

Details of the operations, however, offer evidence that Huawei employees played a direct role in government efforts to intercept the private communications of opponents.

Huawei has “never been engaged in ‘hacking’ activities,” said a Huawei spokesman in a written statement. “Huawei rejects completely these unfounded and inaccurate allegations against our business operations. Our internal investigation shows clearly that Huawei and its employees have not been engaged in any of the activities alleged. We have neither the contracts, nor the capabilities, to do so.”

The spokesman added: “Huawei’s code of business conduct prohibits any employees from undertaking any activities that would compromise our customers or end users data or privacy or that would breach any laws. Huawei prides itself on its compliance with local regulations and laws in all markets where it operates.”

In Zambia, according to senior security officials there, Huawei technicians helped the government access the phones and Facebook pages of a team of opposition bloggers running a pro-opposition news site, which had repeatedly criticized President Edgar Lungu. The senior security officials identified by name two Huawei experts based in a cyber-surveillance unit in the offices of Zambia’s telecom regulator who pinpointed the bloggers’ locations and were in constant contact with police units deployed to arrest them in the northwestern city of Solwezi.

The ruling Patriotic Front posted on its Facebook page in April that police officers working with “Chinese experts at Huawei have managed to track” and arrest the bloggers. The party’s spokesman confirmed to the Journal that the case was handled by the Cybercrime Crack Squad, the unit at the telecom regulator.

The revelations focus attention on the surveillance systems Huawei sells governments, often branded “safe cities.” The company says it has installed the systems in 700 cities spread across more than 100 countries and regions.

In Zambia, Huawei’s products are part of the country’s Smart Zambia initiative to implement digital technologies across government departments.

Huawei, in the statement, said it had never sold safe city solutions in Zambia and hasn’t conducted business with Zambia’s Cybercrime Crack Squad.

Chinese government officials have played a key role in facilitating deals for Huawei in Africa, attending meetings and escorting African intelligence officials to the company’s headquarters in Shenzhen, according to senior African security officials.

While many of the projects are rudimentary, Huawei has sold advanced video-surveillance and facial-recognition systems in more than two dozen developing countries, according to data gathered by Steven Feldstein, an expert in digital surveillance at Boise State University and a former Africa specialist at the State Department.

Huawei lists foreign firms among its partners in its safe-city products, including U.S. smart-sensor manufacturer and systems integrator Johnson Controls International PLC and iOmniscient Pty. Ltd., an Australian producer of AI systems that analyze video, sound and smell. Johnson Controls declined to comment. iOmniscient said it has provided behavioral analytics products through Huawei in the Middle East but not in Africa.

Continental Drift

Huawei is Africa’s dominant supplier of mobile internet networks and state surveillance systems.

National security systems that make use of video surveillance, internet monitoring and cellphone-metadata collection have become widespread. Huawei’s elite systems move beyond that level. According to senior security officials, embedded, hands-on Huawei technicians train security forces and cyber-surveillance units that regularly snoop on political opposition.

“The big question has been whether Chinese companies are just doing this for the money, or whether they’re pushing a specific kind of surveillance agenda,” Mr. Feldstein said, after being briefed on findings by the Journal. “This would suggest it’s the latter.”

Africa’s importance to China “is at least as much about Beijing’s longer-term vision for recruiting foreign countries to embrace Chinese norms of governance in the digital sphere and in terms of its illiberal political values,” said Andrew Davenport, an executive at RWR Advisory Group, a Washington, D.C.-based risk management firm that tracks the international activities of Chinese and Russian firms.

The Journal’s investigation included classified police documents and parliamentary committee documents, and interviews with more than a dozen senior security officials working with Huawei in African countries, and with diplomats, cyber-defense officials and opposition activists who say they have had their communications compromised.

Uganda’s government confirmed Huawei technicians were working with its police and intelligence agencies to bolster national security but declined to comment on the allegations of intercepting communications.

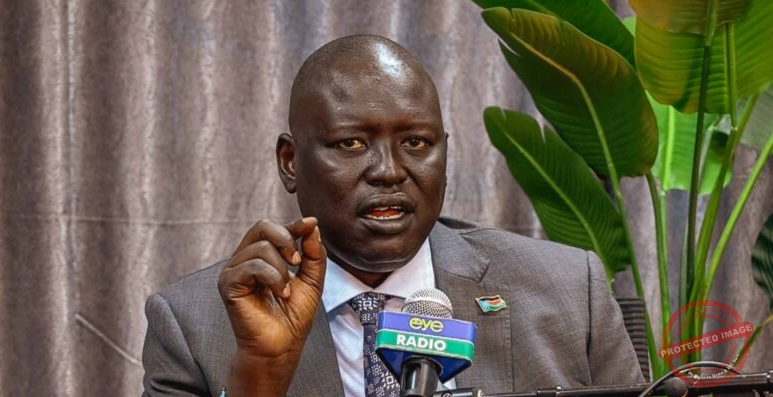

“We are not at liberty to publicly reveal the specifics,” said Ofwono Opondo, a government spokesman. Mr. Opondo denied that the government is targeting Bobi Wine, saying the opposition lawmaker “isn’t such an important issue” to warrant heightened surveillance.

Zambia’s ruling party spokesman, Antonio Mwanza, said Huawei technicians, based inside the Zambia Information & Communications Technology Authority, or Zicta, regulator, were helping the government combat opposition news sites.

“Whenever we want to track down perpetrators of fake news, we ask Zicta, which is the lead agency. They work with Huawei to ensure that people don’t use our telecommunications space to spread fake news,” he said.

Ugandan officials said that Huawei representatives have stopped attending technical briefings since the Journal submitted questions to the Chinese company.

China’s Foreign Ministry said in a written statement that it is common practice for countries to cooperate on policing. “Some African countries have enthusiastically built ‘safe cities’ in order to improve the lives of their people and their business environments,” the ministry said. “To equate this positive effort with ‘surveillance’ smacks of ulterior motives.”

Huawei’s founder, Ren Zhengfei, publicly denied in January that the company spied on behalf of the Chinese government. It was the launch of a global public-relations blitz to counter negative press sparked by the arrest in Canada of Huawei’s CFO and a Trump administration pressure campaign to persuade allies to ban Huawei gear from next-generation 5G networks.

“Neither Huawei, nor I personally, have ever received any requests from any government to provide improper information,” Mr. Ren said at a gathering of foreign journalists.

In May, President Trump escalated the campaign, signing an executive order that allows the U.S. to ban telecommunications gear and services from “foreign adversaries,” a term widely interpreted to refer to Huawei. The Commerce Department added Huawei to the “Entity List,” citing national security concerns, which effectively bars companies from supplying U.S.-made technology to Huawei without a license. The president said last week that business with Huawei may be a factor in U.S.-China trade negotiations.

Huawei has connected hundreds of millions of African consumers since first doing business in Kenya in 1998. It has built telecom networks in some 40 African nations by offering inexpensive deals often financed by loans with favorable terms and by providing on-the-ground customer service. Huawei now dominates Africa’s internet business. In recent years, it has expanded into digital-surveillance systems.

Zambian senior security officials said that in the country’s new $75 million data center, Huawei employees work with the Cybercrime Crack Squad, sitting in cubicles where they monitor and intercept digital communications from a broad spectrum that includes criminal suspects, as well as opposition groups, activists and journalists.

In Uganda’s capital, Huawei has helped build 11 monitoring centers used to fight crime, according to the national police deputy spokeswoman. A new six-story, $30 million hub due to open in November will be linked to more than 5,000 of the company’s cameras equipped with facial-recognition technology.

In one of the rooms at Uganda’s police headquarters, Huawei has its red logo affixed to the wall. “They teach us to use spyware against security threats and political enemies,” said one official at the unit.

A few years ago, the East and Southern African nations appeared to be regional models for web freedom: few rules policed social-media usage or restricted freedom of the press, and there was more competition in the marketplace. Programmers and aspiring entrepreneurs from top U.S. colleges flocked to Kampala to launch startups.

World Power

Huawei has quickly become the largest maker of telecom equipment.

Around 2012, Uganda’s President Museveni began to see the web more as a political risk than an economic opportunity, according to senior government officials and classified documents published by Unwanted Witness, a Ugandan organization working to fight online censorship. Concerned about the mobilizing power of social media and what he called public immorality online, he asked his intelligence agencies to find better tools to monitor the web and muzzle online dissent.

As a crash in commodity prices heaped pressure on Mr. Museveni ahead of his fifth election campaign in 2016, Uganda began to deploy surveillance software, including FinFisher, made by Anglo-German company Lench IT Solutions, which they inserted into the Wi-Fi networks of several of Kampala’s top hotels to penetrate the phones of politicians, journalists and activists, according to the senior government officials and Unwanted Witness.

Lench IT didn’t respond to requests for comment.

The technology had limitations: It didn’t infiltrate devices that didn’t connect to the targeted Wi-Fi networks and couldn’t crack encrypted messaging services like WhatsApp.

Mr. Museveni won the 2016 election but in spring 2017 faced fresh protests over his move to abolish the age limit for the presidency. Mr. Museveni directed then-police chief, Kale Kayihura, to approach the Chinese government to help expand digital surveillance, according to senior security officials.

Huawei had arrived in Uganda in the early 2000s. It won its first major government contract in 2007 and gave the Ugandan government 20 surveillance cameras valued at $750,000 in 2014. At a donation ceremony attended by Chinese government officials, Mr. Museveni thanked Huawei “for its contribution to corporate social responsibility.”

The following year Huawei signed a deal to become the Ugandan government’s sole information-communications partner.

Within weeks of Mr. Museveni’s 2017 order to expand digital snooping on the opposition, Uganda’s communications regulator contracted Huawei to explore setting up a surveillance center with assistance from security agencies, according to senior Ugandan officials.

By May, Uganda’s police force had sent dozens of officers for technical training in Beijing, accompanied by senior Huawei Africa-based employees and a senior Chinese Embassy official, Chu Maoming. After three days the group was flown to the company’s Shenzhen headquarters, where Huawei executives shared details on the surveillance systems it had built across the world, according to Ugandan security officials who were present.

Mr. Chu played a crucial intermediary role in the talks. He accompanied the delegation to meetings with China’s Public Security Agency in the ministry’s cube-like complex near Tiananmen Square, where they were shown the capabilities of the Chinese surveillance state. Mr. Chu then flew with the group to Shenzhen and sat in on meetings with Huawei executives, according to the Ugandan officials present.

China’s Foreign Ministry didn’t address Mr. Chu’s specific involvement in the deal but said in its statement that when the Chinese government welcomes foreign delegations, “it will organize visits according to their wishes, including to companies.” The ministry said such arrangements are common practice around the world. The Chinese Embassy in Kampala didn’t respond to requests for comment.

Huawei executives recommended to Uganda it look at a surveillance system in Algeria, where the aging autocrat Abdelaziz Bouteflika was trying to stare down simmering opposition after almost 20 years in power, according to the Ugandan officials. Mr. Bouteflika was ousted in April this year.

In September 2017, a team of senior Ugandan security officials was dispatched to study the video surveillance system in Algiers, which included mass monitoring and cyber-surveillance centers.

“We discussed hacking individuals in the opposition who can threaten national security,” one of the officials said, adding that Algerians are advanced in that field.

The Ugandan and Algerian forces jointly prepared a classified report, reviewed by the Journal, that calls Algeria’s system “Huawei’s intelligent video surveillance system” and says it is “an advanced system and provides one of the best surveillance applications.”

Later that month, Mr. Kayihura, the police chief at the time, signed a cooperation agreement with Algeria to have an Algerian team advise on the rollout of Uganda’s Huawei-implemented surveillance program. The project’s lead Algerian adviser was described by the Algerians as a cyber expert trained in Huawei’s headquarters in Shenzhen, according to senior Ugandan officials.

Huawei, in the statement, said it had never sold safe city solutions in Algeria.

Algeria’s Foreign Ministry didn’t respond to multiple emails and calls for comment. Multiple visits and calls to the Algerian Embassy in Uganda yielded no comment.

Mr. Kayihura, who has been under house arrest since June 2018 and has been charged with several offenses including illegally distributing government weapons to civilian militia, couldn’t be reached for comment.

In May 2018, Uganda’s Mr. Museveni signed a $126 million deal with Huawei for the safe-cities project after a classified bidding process involving two Chinese companies, paying $16.3 million up front and financing most of the rest with a $104 million loan from Standard Chartered Bank, according to documents presented to a parliamentary committee. Work began in July to construct a digital surveillance unit at Kampala’s police headquarters and to install hundreds more street cameras.

A product brochure on the Huawei website this year said the first phase of Uganda’s project would connect 83 police stations in the capital and be expanded to another 271 police stations across the country.

Some lawmakers raised concerns about the project and its lack of transparency. “There appears to be a policy to hand over the country’s entire communications infrastructure to the Chinese,” Maxwell Akora, an opposition party member of the Ugandan Parliament’s Information, Science and Communication Technology Committee, said in an interview. “It’s unwise given our concerns about spying and creating backdoor channels.”

efore the Huawei project got rolling, in early 2017, Uganda’s security services received a delivery of spyware, according to Ugandan senior security officials. The spyware was modeled on a product called Pegasus, created by Israeli firm NSO Group. Similar products are sold under different names by a number of cyber-intelligence firms. The spyware can penetrate encrypted messages in smartphones, according to Amnesty International.

The Ugandans received training from five Israeli government technicians. Ugandan intelligence officers said they were taught how to use the spyware for reading emails and texts but not encrypted communications.

The Israeli government didn’t respond to a request for comment.

“The training was short-lived and not very sophisticated like what we got from the Chinese,” one senior Ugandan security official said.

Uganda’s first cyber unit opened in November 2018, and Huawei technicians were seconded from the Shenzhen headquarters to train Ugandans how to use the Huawei infrastructure and software and tools in part from other companies to monitor the web, according to Ugandan senior security officials.

Ugandan social media monitors began to send alerts to security chiefs if they detected “offensive communication,” a euphemism for antigovernment rhetoric, on citizens’ accounts, the officials said.

The capability gave Ugandan security officials more visibility into opposition activists’ communications as a wave of protests erupted from a new source: the rapper-turned-activist Bobi Wine. In July and August 2018, Mr. Wine, whose legal name is Robert Kyagulanyi Ssentamu and who had been elected to Parliament in 2017, brought tens of thousands of people into the streets for a series of concerts at which he called for Mr. Museveni to step down. He was arrested and badly beaten, then traveled to the U.S. for medical treatment, where he got support from several congressmen.

In early December 2018, after Mr. Wine returned, a group of Ugandan intelligence officers in the cyber unit picked up wiretapped phone conversations between the pop star and several of the country’s most high-profile opposition lawmakers, according to Ugandan senior security officials.

Mr. Wine appeared to be arranging for the politicians to give speeches at his concerts. But the cyber team monitoring the calls had a problem. They couldn’t decipher the details of the plans because Mr. Wine was speaking to his team using a coded street slang.

A senior police commander relayed a presidential order to access Mr. Wine’s encrypted written and spoken communications, including those through WhatsApp and Skype, to a six-man cyber team based at police headquarters, according to the security officials. They spent days trying to penetrate the communications using the spyware but failed.

They asked for help from Huawei technicians—who then cracked Mr. Wine’s encrypted communications using the spyware within two days, the security officials said.

“It was very clear he was organizing a political event, not a music show. We had to act quickly,” one of the officials said.

In a WhatsApp chat group, Uganda’s cyber team saw a list of 11 lawmakers Mr. Wine was planning to secretly insert into the concert program. The rally, at Mr. Wine’s beach club, was scheduled unusually early to throw off the security services. Using information from the cyber hub, hundreds of police swarmed the venue, arresting dozens of organizers and attendees. Some were arrested before they could reach the club.

“We were shocked. They knew everything about the event and the speakers, who we hadn’t announced,” Mr. Wine said.

One of the security officials showed the Journal screenshots of Mr. Wine’s WhatsApp chats with the Firebase crew where participants were exchanging details on the planned events. The official said the operation would have been impossible without the skills of Huawei’s technicians.

Mr. Wine, whose attempts to organize subsequent rallies have also been foiled, said the surveillance has spread to his family, his entourage and the people who frequent bars where his music is played. He now switches between several phones and uses devices of sympathetic members of the public, but he said he is outgunned by Mr. Museveni’s expanding machine.

“The deal with Huawei is a survivor strategy to consolidate power,” he said in an interview in his Kampala home. “It’s an all-out assault.”

A similar story unfolded in Zambia.

The first phase of the project, worth $440 million and mostly financed by the Export-Import Bank of China, began in 2015 after President Edgar Lungu traveled to Beijing to meet President Xi Jinping. Since 2016, Huawei has led the construction of an information and communication technologies training hub and hundreds of cellphone and data connection towers.

Huawei has also established a data center complex at Zicta, the telecom regulator, said Brian Mushimba, Zambia’s minister of transport and communications, in a telephone interview with the Journal.

On the second floor of Zicta’s gray-colored facility, behind biometric scanners, Huawei employees are embedded within Zambia’s new data center, which houses the Cybercrime Crack Squad, Zambian security officials said. Established in February, around half of the 40-strong staff at the data center are Huawei employees, two Zambian officials there said.

In April, President Lungu’s office ordered a crackdown on news sites that had published a string of damaging stories. Zambia was for decades seen as one of Africa’s most stable and permissive democracies, but in recent years it has moved to muzzle opposition media, shuttering some of the country’s top newspapers and television channels and pushing antigovernment voices onto Facebook sites and WhatsApp forums.

Mr. Lungu’s press secretary, Amos Chanda, called the head of the cyber squad, Mofya Chisala, and a senior chief Huawei technician for help, Zambian intelligence officers said.

Mr. Chanda said he had “no recollection of the events or meetings” with the cyber squad or Huawei officials. Mr. Chisala didn’t respond to requests for comment.

Huawei technicians helped intercept the communications of opposition bloggers running a news site named Koswe, or “The Rat,” which had repeatedly criticized Mr. Lungu, the two Zambian officials in the Cybercrime Crack Squad said.

The Huawei staff accessed the bloggers’ Facebook pages, where they found their phone numbers, and then used spyware from another company to look into and locate the devices.

On April 18, a team of cyber officials, police intelligence and Zicta experts huddled in Mr. Chanda’s office, on the ground floor of the presidential mansion. Two Huawei technicians opened their laptops to display screens showing live trace routes of several mobile phones linked to the targeted bloggers’ Facebook pages, on maps that also charted Huawei phone antennas, Zambian intelligence officials said.

The cyber squad alerted the police in the northwestern provinces where Huawei had pinpointed the opposition bloggers.

Over the next few days, Huawei experts helped Zambian officials track the targets from the Zicta data center offices, maintaining real-time contact with police officers in the field, the intelligence officials said.

Finally, police swooped in on sites on the outskirts of the copper mining town Solwezi. One suspect was typing on his laptop when officers burst in and seized his electronic devices.

“We found one of the suspects editing a long, malicious article which he was about to post,” one of the intelligence officials said.

One official on the cyber squad said the Zambians have “nowhere near the expertise” of Huawei.

(Report: Joe Parkinson, Nicholas Bariyo and Josh Chin | Wall street journal)