Over the years, there has been debate over how many children actually drop out of learning, over a school cycle. So, SAMUEL KAMUGISHA sat down to study the enrolment figures at the education ministry and came to a startling conclusion.

Over five million Ugandan children of school-going age have dropped out of primary school before P7 in the past 20 years. This is according to an analysis of figures from assessment body Uganda National Examinations Board (Uneb) and Education and Sports Sector Annual Performance Reports (ESSAPRs).

The number of school dropouts has been increasing over the years

The Uneb figures of these unaccounted-for pupils span 20 years of the school calendar and 15 Primary Leaving Examinations (PLE) sittings between 1995 and 2015 – final examinations from 2001 to 2015. On the other hand, the analysis of ESSAPR figures captures eight school cycles in 15 calendar years.

According to the Uneb figures, in just two decades, about 12.2 million pupils started primary one but only 6.95 million (57.2 per cent) completed their primary schooling cycles – over 5.2 million (42.8 per cent) dropped out. This means that at least 43 out of every 100 (or four out of every 10) pupils, who started school, dropped out before completing P7.

Thus in the 15 years (eight primary school cycles) over 4.9 million school children (about 42.6 per cent) of the 11.5 million who started school dropped out.

WHAT THE FIGURES MEAN

According to the 2014 population census figures, Uganda’s population stands at just over 34 million. This means that over 15 per cent of the country’s population size comprises primary school dropouts – young men and women who have not attained a Primary School Certificate. This is equivalent to the total population size of Kampala, Wakiso, Kibaale and Arua districts – Uganda’s most populous districts.

On average, between 1995 and 2009, of the over 810,000 pupils who started school each year, close to 350,000 did not complete the school year cycle. For each of the 20 years analysed (which make up 15 school cycles), just over 250,000 left school each year, on average. The pupils dropping out of school each year is equivalent to about a half the population of Kabale, Uganda’s ninth most densely populated district.

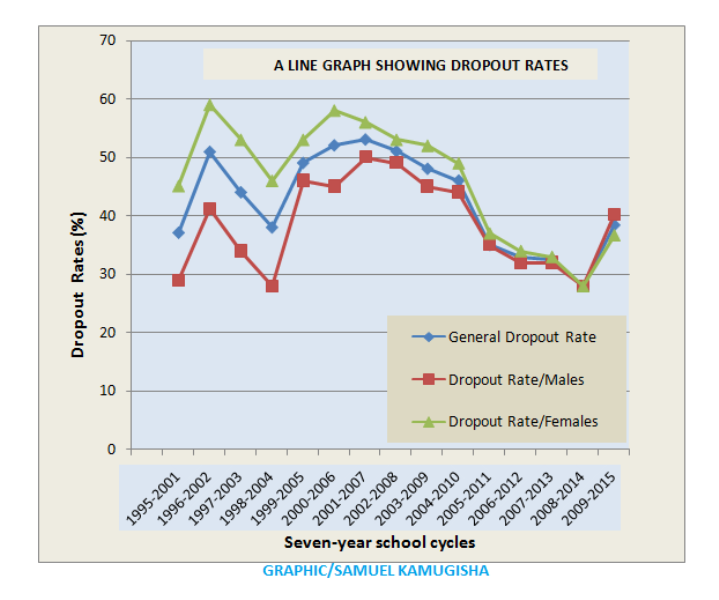

MORE GIRLS OUT OF SCHOOL

The dropout rate is more worrying for girls than boys. Of the 6,243,532 female pupils who went through the 15 primary school cycles (P1-P7), only 3,347,348 (53.6 per cent) completed primary seven, while 2,896,184 (46.4 per cent) dropped out. The number of female dropouts is equivalent to the total population size of Arua, Kasese, Mubende and Mukono districts of Uganda.

The dropout rate for girl learners was just above the general average dropout rate of 42.8 per cent. For seven school cycles, just over a half of the number of female pupils who started primary school did not complete.

These learning cycle years were: 1996-2002 (59 per cent); 1997-2003 (53 per cent); 1999-2005 (53 per cent); 2000-2006(58 per cent); 2001-2007(56 per cent); 2002-2008 (53 per cent); 2003-2009 (52 per cent).

For three more cycles, the dropout rate was above the average of 42.8 per cent but not above 50 per cent: 1995-2001 (45.1 per cent); 1998-2004 (46 per cent); 2004-2010 (49 per cent).

However, between 2005 and 2014, the dropout rates for females reduced slightly, then steadily, from 37 per cent (about 149,000 dropouts) in the 2005-11 cycle; to 34 per cent (over 138,000 dropouts) in 2006-12; to 33 per cent (about 136,800 female pupils) in 2007-13; to 28 per cent (over 113,000) between 2008-14.

The steady reduction in the dropout rates was however interrupted by a retention reversal in the 2009-15 cycle with the dropout rate rising to 36.7 per cent (about 178,000 dropouts).

The steady reduction in the dropout rates was however interrupted by a retention reversal in the 2009-15 cycle with the dropout rate rising to 36.7 per cent (about 178,000 dropouts).

MALE DROPOUT RATE

Although more girls dropped out of school before primary school completion, the situation was not any rosy for their male colleagues.

Some 44.2 per cent of the learners who had left school before sitting PLE were boys. Just like the rate of female dropouts, the rate for male dropouts is also higher than the average rate of 42.8 per cent over the 15 primary school cycles – a reminder that the issue of school dropout rates is not necessarily a gender issue: male pupils equally need attention.

For the 2001-07 school cycle, half of the number of male students who started primary one, dropped out before P7. By the end of the 2007 calendar year, some 217903 boys (50 per cent) of the 435806 who started Primary one in 2001 had left school.

For four other cycles, the dropout rate for males was just above the average rate of 42.8 per cent: about 46 per cent (186,515 male pupils) in the 1999-2005 cycle; 45 per cent (175,216) in the 2000-2006 cycle; 49 per cent (227,488 boys) in the 2002-2008 cycle; 45per cent (202,741) in the 2003-2009 cycle; and 44 per cent (196,048) in the 2004-2010 cycle. Although above the average dropout rate, there was a slight reduction in the dropout rates for the three latter cycles (2002-2008, 2003-2009, and 2004-2010).

The dropout rate fell even more further in the following school cycles to 35 per cent (140,686 dropouts) in the 2005-11 cycle to 32 per cent for both 2006-12 and 2007-13 cycles and 28 per cent (114,349 dropouts) in 2008-14 cycle.

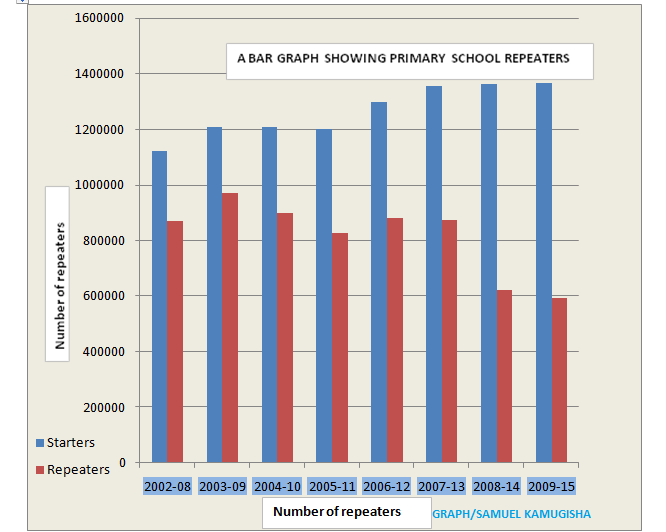

CLASS REPEATERS

Besides the dropout numbers, the ESSAPR reports also give a clue of how many pupils stay longer in the primary school cycle. The education ministry expects learners to start primary one at age six and complete primary seven at age 13.

ESSAPR reports for eight school cycles indicate that in just fifteen years, 6.6 million of the 11.5 million (57 per cent) who started school had repeated more than one class. This means that about six out of every 10 pupils are likely to repeat at least one class level before either finishing primary school or dropping out.

Although the Uganda government discourages schools from making pupils repeat, most private schools have not heeded the policy on non-repetition of class. And as education sector reports indicate, “increased repetition rates” is just one of the reasons why pupils never complete primary education – some of the other reasons being teenage pregnancies and early marriages.

WORST YEAR CYCLES

Overall, the 2001-2007 cycle was the worst year for boys with over a half of those who started primary one dropping out before completing primary seven. On the other hand, the 1996-2002 cycle saw the highest rate of girl dropouts out of all the 15 cycles at 59 per cent.

The highest number of pupils leaving school before completion was registered in the 2002-2008 cycle. Almost half a million learners dropped out.

UNEVEN EXPLANATION

In the past, education ministry officials have been wont to explain away the discrepancies through the process of repetition. However, the ESSAPR report now indicates that very few pupils actually repeat their classes – an average of 10,000 per year.

ESSAPR reports for eight school cycles indicate that in just fifteen years, 6.6 million of the 11.5 million (57 per cent) who started school had repeated more than one class. This means that about six out of every 10 pupils are likely to repeat at least one class level before either finishing primary school or dropping out.

The education ministry expects learners to start primary one at age six and complete primary seven at age 13. Asked about the discrepancy, the current acting director for Basic Education, Dr Robinson Nsumba Lyazi, confessed he had not studied the enrolment numbers but agreed that it was cause for concern.

“We need to determine how many children are falling out of the system and find a solution for this quickly,” he said.

However, Dr Christian Kakuba, a lecturer in Population Studies at Makerere University, who has studied the matter, argued that it was a serious problem that needs urgent remedy.

“It is unacceptable to be losing so many learners, who have the potential to improve this country,” Dr Kakuba said. “Something must be done urgently.

Angella Nabwowe of the Initiative for Social and Education Rights agreed.

“The study makes for a very sobering situation … sometimes you wonder what happened to the people you went to school with, and to think they fell by the wayside is hard to take,” she said.

A truncated Version of this special report was first published by The Observer